by Joyce H. Munro

Music for stargazing: “Concierto De Aranjuez,”

The Modern Jazz Quartet with Laurindo Almeida

For I am Merope,—rash Merope,—

She that was great in Heaven become the least,

Standing between God’s lowest and God’s love.

(“The Lost Pleiad,” Sir Edwin Arnold, 1856)

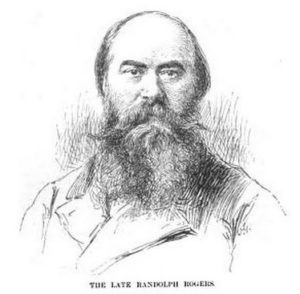

If I had a 3D printer, I could recreate Randolph Rogers’ Lost Pleiad and place her on a pedestal in my home. She would be much smaller than life-size, of course, and not of marble, but no matter. She would be mine. I’d create her in palest ice blue because that’s how she appears in the heavens.

But why make only one? Doesn’t everybody want to own a star, especially a lovely lost one? Heck, I could extrude enough nontoxic star-statues to fill a souvenir shop in Rome. Galactic purple, stellar pink for the romantics, aurora green. Iridescent statues will cost more.

Rogers had the same notion, except he placed a strict limit on the number and size of his replicas. In fact, he offered two sizes only—life and half-life. White only. Of marble only. He never envisioned Lost Pleiad as a trite, rubbery souvenir.

2013

The first thermoplastic Lost Pleiad was the creation of a clever techie at the Brooklyn Museum. Quite a feat. What Rogers molded of clay and turned to burnished marble is now made synthetic and pliable. She can bounce without breaking.

Lost Pleiad, courtesy of Thingiverse.com

§§§§

Within the Pleiades star cluster (aka the Seven Sisters), there is one sister who has an uncanny ability to shine without being seen. She is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. Actually, she is wrapped in a murky haze, and at times the darkness hides her. That’s how it is sometimes in astronomy—the brightest can be the hardest to see.

Ancient Greeks named her Merope, this cheeky daughter of a god who exiled herself by marrying a mortal (impetuous meet impious) and, when that didn’t work out, headed back home. Some say that she finally hooked up with her family, but whenever she’s overcome with shame, she blushes and goes into hiding.

Others say a reunion wasn’t in the stars for Merope. Forever an outcast, her hapless search for family will never end. Sadder still, her sisters in the starry skies will not miss her.

Bow’d be our hearts to think of what we are,

When from its height afar

A world sinks thus—and yon majestic heaven

Shines not the less for that one vanish’d star!

(“The Lost Pleiad,” Felicia Dorothea Hemans, 1825)

Such a cosmopolitan, yet chaste, story. Heart-rending, with a streak of enmity running through it. And what if I tell you Merope looks like a teardrop to some astronomers?

This is the Merope Rogers chose to sculpt. No wonder he chose polar white marble. No wonder he chose Hemans’ cautionary poem to enclose in letters to those who purchased her. Never let it be said Rogers wasn’t a savvy marketeer of his sculptures.

1882

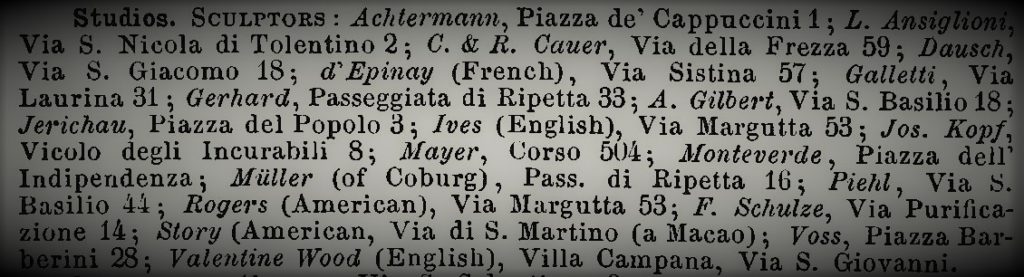

When Philadelphia industrialist-civic promoter John Thompson Morris first laid eyes on Lost Pleiad, he was on Roman holiday with his sister Lydia. He was thirty-four years old, he had walked those cobbles before, and he knew exactly where to find her, thanks to his handy copy of Italy, Handbook for Travelers.

As he gazed upon this woman-nymph-star floating on a cloud in Rogers’ sculpting room, I have my doubts that Morris was thinking of cultural custodianship.

§§§§

I suspect he was blown away, as so many were when they saw this “marvel of execution.” He may have even blushed (as he undoubtedly did late one night when he and a French lady were alone in the reading room of a Rome hotel and somebody turned out the lights—imagine what E.M. Forster could have written into that episode). I think Morris knew immediately he had to have this lovely lost star for his own. Here’s why I think this . . .

Consider his course of action immediately after making the purchase: he had Lost Pleiad shipped to his townhouse, not to the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, as was his habit with curiosities found while traveling. As he had done the previous year at the Milan Exhibition, where he bought a bronze bell by the famed De Poli brothers of Vittorio and promptly turned it over to the museum, with an exhortation to fellow members:

. . . if each traveler would bring home an object for the Museum, it would help with the good work. New Yorkers are remembering their museums, and why should not Philadelphians do the same with ours?

Not this time. She was not meant to be a museum piece; she was meant to take home. But no trivial souvenir this. He would pay full price—plus thirty-percent duty. And he would make space for her. In the center of the room. Set her on a pedestal. Walk around her. Pass by her on the way to the dining room. Sit in a chair and study her. Come close and try to catch her eye.

Except she is looking for someone else. Did he call her Merope, this heaven-exiled sister? This poor dove who had wandered far from her nest.

When you see

O’er darkened graves, at eve, a mystery

Of pale, soft, luminous light, now here, now there,

Now flickering o’er a mound, now in the air,

Believe it is Pleiad, who would fain

Join her sweet sisters up in Heaven again.

(“The Moon and the Pleiades,” Augusta de Bubna, 1879)

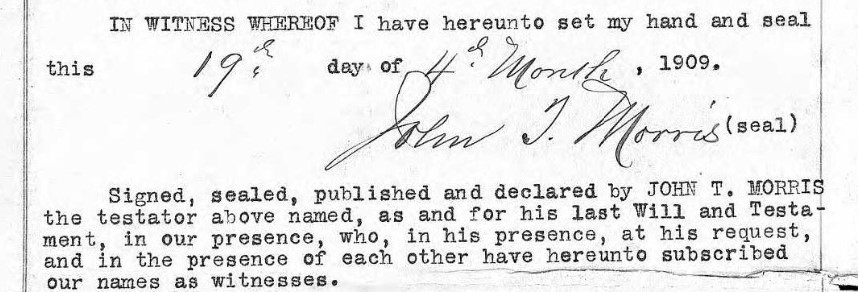

Consider also Morris’ course of action years later: Though he owned a number of statues, Lost Pleiad was the only one named in his will. Not only did he spell out where she was to reside, he gave directions for how she was to be treated:

It is also my desire that special and careful provision be made for the display in a separate room of my statue of “The Lost Pleiad” by Randolph Rogers, arranged as the same is now displayed in my house, with the addition of a plate glass to protect it from dust and handling.

But occasionally, she may leave home—“responsible” museums could borrow her if she was kept behind a door with a time lock; she must be returned immediately if she was not properly displayed. And to these crystal-clear instructions, he signed his name:

But there is another notion that could hold sway. What if Morris didn’t want Lost Pleiad for himself? There was another tourist in Rogers’ studio the day he bought her. His sister.

Art historians—Lauren Lessing among them—inform us that nineteenth-century idealistic statues, of which Lost Pleiad is an example, appealed to women patrons. Women were Rogers’ clients too. Women like heiress Jennie McGraw of Ithaca. Women like Lydia Thompson Morris, who may have wanted Lost Pleiad more than her brother. Could it be that Lydia was the patron and her brother merely paid the bill?

Could it further be that, unlike Jennie McGraw who was on a worldwide shopping spree for her colossal new home and wanted a statement sculpture for the art gallery, Lydia wanted her for a different reason. Of all the sculptures in Rogers’ studio, is this the one that took her breath away? Is this the one that triggered her own loss and aloneness?

Lydia knew what loss felt like. The wasting away of family from consumption, bilious fever, stroke. The shame of family who abandoned their long-held Quaker tenets in order to do business in the world and were, forever after, out of unity with their own religious community.

Or did Lost Pleiad hit a deeper vein, something made of harder stuff in Lydia? Her allegiance to family and social causes dear to her heart. Her obligation to find and handle antiquities of the world responsibly. Her resolve to salvage Cedar Grove, a humble homestead, relic of Colonial times, every board, every stone. Lydia knew something about determination. So did Merope.

1860

Flitting moments, imminent emergencies, imperceptible intervals between two breaths, ought not to be encrusted with the eternal repose of marble; in any sculptural subject, there should be a moral standstill, since there must of necessity be a physical one. Otherwise, it is like flinging a block of marble up into the air and, by some enchantment, causing it to stick there. You feel it ought to come down, and are dissatisfied that it does not obey the laws of nature. (The Marble Faun, Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1860)

Did Hawthorne see this crime of encrustation taking place in the Rome studio of an American ex-pat? Did he stand there smirking at the chiseling of a star into a shape too restrictive, too impossible?

1851?

Her face had “the expression of angels,” said E. R. Keyes, the aide-de-camp to General Winfield Scott. Keyes claimed he had never beheld a child “more lovely in shape and countenance.” He was speaking of the general’s daughter, Adeline Camilla Scott, then in her teens.

Look at the face of Lost Pleiad. Do you see what Keyes saw?

You should—that’s Camilla’s face. And that’s Camilla’s body. Some say she modeled for Rogers in 1874. But if so, her body had defied all laws of nature because she was then in her forties and mother of six children. So here’s another notion: Camilla was in her twenties when she modeled for Rogers. Here’s why I think this . . .

Consider her form a decade earlier when she was in her thirties and mother of three and an acquaintance opined: “That lady grows stouter than is becoming, but her face is among the most splendid specimens of physical beauty—for form and color—I have ever seen.”

Now consider her form two decades earlier when she was in her twenties, walking the aisle at her wedding to Goold Hoyt in Washington, DC, and a guest reported she was “one of the most beautiful women I have ever known, her face reminded me of a Roman cameo.” And was it during the newlyweds’ extended tour of Europe that Rogers spotted her sipping coffee at a trattoria or strolling along Via Margutta or shading her eyes from the sun, and he knew immediately he had found his Merope.

Lost Pleiad by Cliff at Flickr

1877

There comes a point in marble carving when things in the studio look quite gruesome to unenlightened tourists. Over here stands the plaster cast, stuck with dozens of tiny nails; one would think she has chickenpox. Nearby looms a block of marble, shapeless and waiting, encased in gallows-esque scaffolding. This is when the pointing machine—a torturous-looking instrument with three articulating arms and steel spikes for fingers—becomes necessary. What happens next could be called disfigurement. But do not be repulsed. Col. William Wilkins saw the execution taking place and reassured readers of the Detroit Free Press that Rogers’ masterpiece would live far into the future.

1882

Never let it be said Rogers didn’t care what became of his statues once sold. In July of 1882, he wrote to Morris acknowledging receipt of final payment for Lost Pleiad:

I send you a rough sketch of my idea for lighting the statue. It will not do to have the light fall directly over the head of the statue. In my letter of June 20, I mentioned that I had made a new pedestal as you desired with thicker base and cap. I shall be glad to hear that the statue is safe on its pedestal.

1883

Never let it be said Rogers actually chiseled the sculptures bearing his name, as a tourist from London witnessed the day he walked through the barn-size doors of the studio in 1883:

Although Rogers was ill and absent the work went right on. That is the beauty of sculpture as a profession. When once you have your clay figure modeled you don’t need to touch anything afterwards but the cash.

Oh snap.

1884

What does a star turn into when she’s captured in a medium like marble? “Materialized zephyr,” said Henry L. Sheldon in a Honolulu newspaper. Under the skin she’s nothing but air. Sheldon had seen Rogers’ original Lost Pleiad up close and personal, maybe in Rome or maybe in San Francisco, after she had crossed the ocean to reside at the home of his friend, Theodore Shillaber. She struck Sheldon as ethereal, akin to Thomas R. Gould’s West Wind.

1885

Let it also never be said Rogers’ wife didn’t defend this business of making replicas. Before going into details, I must set the stage by saying shame on Morris for not getting his facts straight the day he bought his. It took him three years to get back in touch with Rogers, and knowing Morris, his letter was peppered with questions: Is my statue identical to the original? Is it exactly the same height? What type of marble was used? Will extreme heat or cold harm the marble? How do I clean my statue?

Rogers never responded. Shortly after selling Lost Pleiad to Morris, he suffered a debilitating stroke. He could no longer hold a chisel or a pen and it was up to Rosa Rogers to write back to Morris on her husband’s behalf:

Neither your statue nor the one at the Cornell University are the first made; that was sent to California in 1875 or 76. One however is as original as another since they are exact copies of the mould made over my husband’s clay model. The copies never vary a hair’s breadth from the model. The marble is Seravezza, a quarry in the Carrara mountains . . . To clean the statue use a strong solution of soda with a moderately stiff paint brush and then wash off with clear water.

How often does an owner need to give a marble statue a sponge bath?

§§§§

Here is where Rogers’ Lost Pleiad has been found:

Ann Arbor Brunswick, ME Brooklyn Chicago Detroit

Falls Church, VA Glendale, CA Kansas City Madrid Minneapolis

Philadelphia Pittsfield, MA Rumson, NJ Sacramento San Francisco

Washington, DC

Jennie McGraw’s Lost Pleiad made her way from Ithaca, New York, to Wisconsin in 1891 and subsequently vanished.

1926

Soon after purchasing Lost Pleiad, the Morris siblings built Compton, their summer home in the Chestnut Hill suburb of Philadelphia, and she took up residence in a more spacious place. Guests such as Rev. Alfred Duane Pell of New York (who famously refused to have his 7000-square-foot mansion centrally heated to avoid damaging his enormous porcelain collection) would have certainly commented on her. So too would Lady Mary Balfour of Suffolk, England, who came to Compton to compare notes on organic farming.

Over a thirty-year period, the Morris siblings were “Philadelphians Abroad” fifteen times. They bought so many objets d’art for themselves that Morris called their townhouse on Pine Street a junk shop. And they bought even more for the city’s art and history museums. But without a doubt, Lost Pleiad was optimus omnium—so prized that Morris wrote Rogers a letter of thanks; it gave him tremendous pleasure to possess her. So prized that he directed she be raised up on a pedestal and protected by a wall of glass.

Compton was supposed to be her final home. She was supposed to have a room of her own. The public was supposed to come into her room and gaze at her free of charge (well maybe they should pay five cents), because Compton was supposed to become a museum. But final doesn’t always mean final-final, for her owner’s directives were never carried out.

After Morris’s death in 1915, Lydia, her four servants and Lost Pleiad continued to live at Compton. A loose cluster of six sisters, all moving together through time. Then Lydia decided to let go of the brightest sister.

And today—in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the museum Morris searched the world over to help fill—this lost star stands. In the center of the room. On a pedestal. You can walk around her. Sit in a chair and study her. Come close and try to catch her eye.

But she is looking for someone else.

O Sisters, lead me with the sound of song,

Sweep solemn music forth from balanced wings,

And leave it cloudlike in the fluttered sky,

That I may feel and follow.

(“The Lost Pleiad,” Sir Edwin Arnold, 1856)

Lost Pleiad, courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

~

This essay is made possible thanks to archival records at the Morris Arboretum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

About the Author

Joyce H. Munro’s work can be found in Broad Street Review, NewsWorks, Hippocampus, Minding Nature, The Copperfield Review, Topology and elsewhere. She writes about the people who kept a Philadelphia estate running during the Gilded Age in “Untold Stories of Compton” on the Morris Arboretum blog.