“. . . the art of how you tell a story is often as meaningful to the audience and as moving to the audience as the story itself.”1

—Julie Taymor, Director and Costume Designer for The Lion King

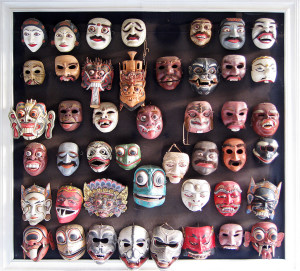

On a recent visit to the Haas Library Archives at Connecticut State University, a shadow puppet and a mask caught my attention. Little information about them was available, but subsequent investigation suggests that they are from Indonesia. In the United States, puppets and masks may often be thought of as mere toys, reminders of Sesame Street, Halloween, or, perhaps, Mardi Gras. Yet, they have a long history of significance in cultures across the world.

According to Jukka Miettinen in Asian Traditional Theater and Dance, shadow puppet theater on the island of Java, at the center of Indonesia, dates back to AD 907. It is there that an old form of shadow puppetry known as wayang kulit originated. Still popular throughout Asia today, it is the aesthetic foundation from which Javanese theater has developed. The traditions of wayang kulit include an emphasis on symbolic and philosophical meaning, and for both the performers and the audience, it is often a spiritual practice. Performances may be watched from either side of the screen upon which the shadows are cast. The stories typically follow a standard plot in which a main character faces conflict with others and within himself and emerges victorious. Serious themes highlight ethical considerations, and while noble qualities predominate, comedy and satire are included as well.2

In Masks, Faces of Culture, John Emigh writes that the use of masks and puppets in the theaters of Indonesia honors ancestors and emphasizes the relationships between the past and present. Masks are used in a style of dance known as Topeng. This Balinese tradition, in its present form, may date back to the seventeenth century. Like wayang kulit, it is a storytelling art and masks are used to represent the different characters. In its oldest form, characters are portrayed by one man, exemplifying the idea that every archetype— good or evil, young or old, brave or cowardly, foolish or wise—is an aspect of the self.3

The effective use of puppets and masks, derived from ancient traditions, contributed significantly to the success of Broadway and traveling productions of The Lion King, which have elicited a wide range of varied and nuanced emotion from millions of people in contemporary audiences around the world. Julie Taymor spent several years in Indonesia, and the arts of wayang kulit and Topeng were influential in her work as director and costume designer of The Lion King. She said on NPR that she was inspired by “the view that the process is as important as the final product in a creative work, that puppetry is one of the highest art forms, and that performing is a vital part of everyday society.”4 In her book The Lion King: Pride Rock on Broadway, Taymor comments on her approach:

Stage mechanics would be visible. . . the rods, ropes and wires that make it all happen. . . The audience, given a hint or suggestion of an idea, is ready to fill in the lines, to take it the rest of the way. Magic can exist in blatantly showing how theater is created rather than hiding the “how.”5

In an interview with Rebecca Gross of NEA, Taymor said, “The first theater artists…were there to understand loss, birth, death, illness, and to take people through the passages of their life.”6

Themes of antiquity live on in the ageless hero quest of Simba, protagonist of The Lion King. The view of a well-executed performance aligns with a meaningful story, and the observer integrates literal, physical experience with a sense of what is timeless and universal. The best artists encourage and inspire us to negotiate complex passages “through despair and hope, through faith and love, till we find our place on the path unwinding.”7

My thoughts return to the mask and shadow puppet in a library basement: how they may have been used, where they had been, and how far they had come.

References

1. Julie Taymor, interview by Rebecca Gross, National Endowment for the Arts Magazine 4 (2011), accessed July 21, 2016, https://www.arts.gov/NEARTS/2011v4-what-innovation/julie-taymor.

2. Jukka Miettinen, “The World of Shadows and Puppets,” in Asian Traditional Theater and Dance (Helsinki: Theatre Academy Helsinki (TeaK), 2010) accessed July 16, 2016, http://www.xip.fi/atd/indonesia/wayang-the-world-of-shadows-and-puppets.html.

3. John Emigh, “Theater,” in Masks, Faces of Culture, eds. John W. Nunley and Cara McCarthy (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999), 224.

4. Julie Taymor, National Press Club, NPR.org, November 15, 2000, accessed July 22, 2016, http://www.npr.org/programs/npc/2000/001115.jtaymor.html.

5. Julie Taymor and Alexis Greene, The Lion King: Pride Rock on Broadway, (New York: Hyperion / Disney Enterprises, Inc. 1997), 28-29.

6. Julie Taymor, interview by Rebecca Gross.

7. “‘Circle of Life’ Lyrics,” Lion King Unofficial World Wide Web Archive, accessed August 16, 2016, http://www.lionking.org/lyrics/OMPS/CircleOfLife.html.

Catherine D’Andrea

Associate Editor