by Elizabeth Edelglass

Son Shoots Father

Wife Takes Blame

July 29. Max Katz, East Side moneylender and bail bondsman, was shot dead yesterday in the Essex Street apartment of his long-time mistress, Fanny Siegel. Miss Siegel declared that Mr. Katz’s wife, Mildred, had done the shooting, but in a statement before he died, Mr. Katz identified his son, Jacob Katz, as the perpetrator. The wife and son were still in the apartment, door smashed in, when police arrived, and they were subsequently arrested.

Detective Patrick Donnelly said the shooting was likely the result of a longstanding disagreement between Mr. Katz and his family concerning his relationship with Miss Siegel. He acknowledged the city’s heatwave could have contributed to the crime. Temperature yesterday reached 97.8˚, surpassing the record set in 1892.

Several hours before the shooting, Miss Siegel called at the Seventh Precinct to request protection from Mr. Katz’s family. But the police found no credible evidence to investigate. Later that night, it was Mr. Katz police found in bed at the Essex Street apartment with a gunshot wound to the chest.

Detective Donnelly quoted Miss Siegel as saying: “It was the wife. She shot him.” But Mr. Katz identified his son, Jacob Katz, as the one who had fired the shot. He then succumbed to his wounds.

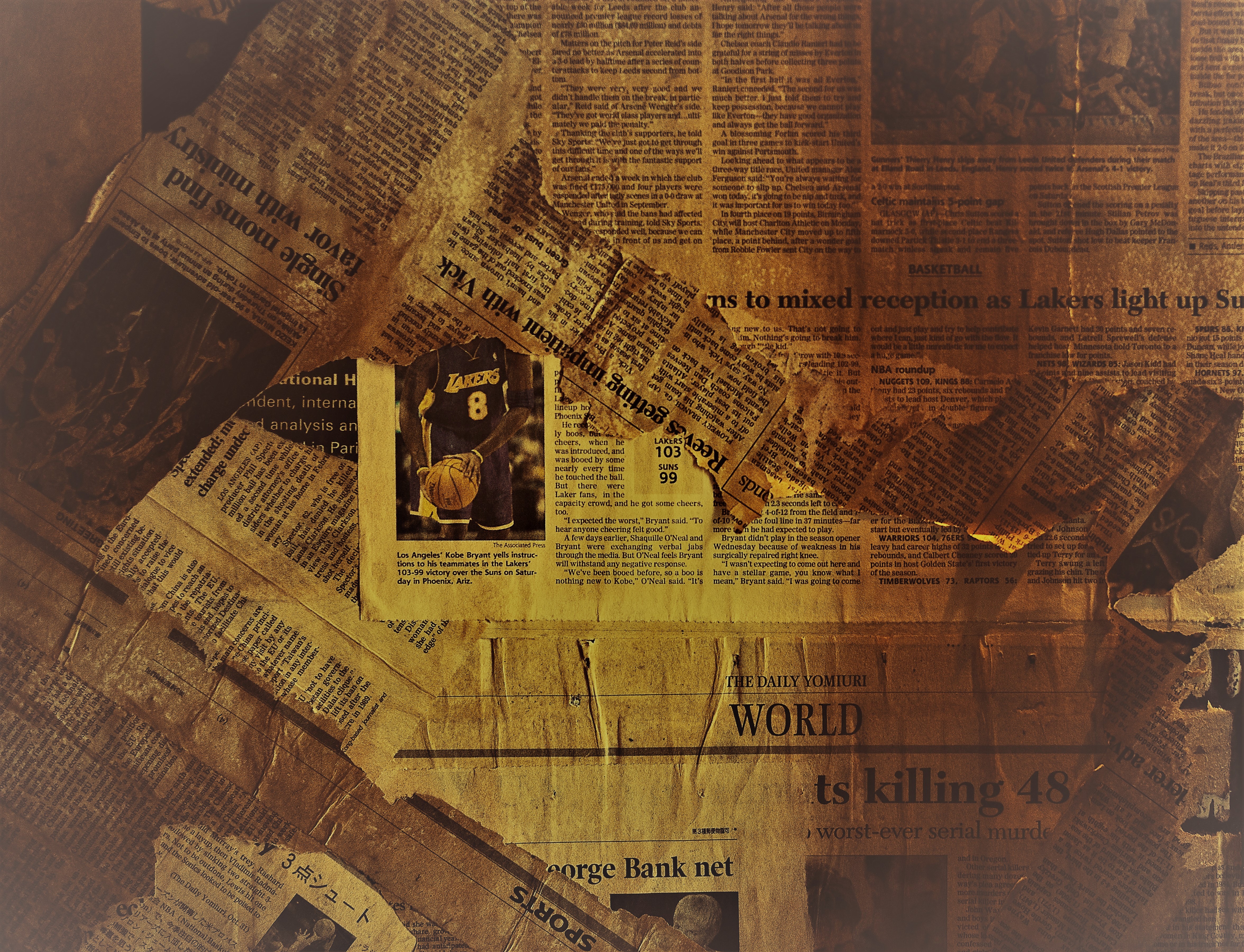

Ruth Weiner was cleaning out her aunt Fanny Siegel’s apartment when she found the newspaper articles, yellowed yet carefully preserved in folded tissue. But that would come later, in the bedroom at the back of this long, narrow apartment, the kind they used to call a railroad flat…or a shotgun apartment.

First, Ruth found the cash, a dollar here, a twenty there. Starting with the coat rack just inside the front door. Coat hooked over coat, all black, some old and heavy enough to have outfitted the tsar’s army, so many pockets, who needs a bank? Coins and bills amongst crumpled tissues, blotted imprints of Fanny’s blood-red lips. Old-lady insurance, not so different from how Ruth used to tell her girls, on dates with high-school boys, all arms and fingers, to carry a payphone dime in their penny-loafers, just in case.

Fanny wasn’t Ruth’s actual aunt, but her mother’s cousin, both arrived from Europe during what Ruth taught her sixth-graders was called the Great Migration, as if they’d been songbirds instead of women. First Fanny, to line up with the girls at sewing machines. Then Ma, younger, yet already married, vomiting in steerage, then a baby, Ruth. Then the political winds shifted, and the doors slammed shut. So, they kept each other close, Ma and Fanny, like sisters.

Until death. Last month, Ma, after long lingering from a lump she hadn’t wanted to bother anyone about. Now Fanny, as if she couldn’t wait to follow, suddenly dead at eighty-four from a broken hip and head cracked against pavement. Crossing the street in front of her apartment, the policeman who phoned had told Ruth. How did you get my number? Ruth hadn’t thought to ask.

Fanny. On the street. Powdered face white against the black pavement. Hairpins scattered, black purse lost in the gutter. Better to picture young Fanny, the only person in America close enough, by blood, to have looked like Ma, only better, rouged and corseted and raven-brunette. Never mind Fanny was older than Ma, her single status had always made her seem younger to Ruth. Independent Fanny, workingwoman out in the world, no slave to household washing and baking.

Whatever Ruth had expected to find in Fanny’s apartment, it wasn’t the blackened pans and sensible shoes she’d emptied out of her mother’s last month. Hard to believe Ruth had never been to Fanny’s apartment before, Ma and Fanny close as sisters, but one married and one not, the rules of their relationship as if codified by the Bintel Brief, a sort of Yiddish Dear Abby. The family didn’t come to Fanny; Fanny came to the family, on the bus to New Jersey, with gifts in her pocketbook, handmade ragdoll, hand-tatted hankie. Now Ruth worked room-to-room, leaving behind the same piles she’d left at Ma’s—give-away, throw-away, anything worth keeping?—surprisingly familiar clutter seemingly stirred by wind whipping past rattly windows.

It was January 1977, would prove to be the coldest on record, but in Fanny’s apartment, it might’ve been July, steam pouring from radiator valves rusted open. Ruth stripped off her cardigan in the parlor over old newspapers and cash under couch cushions, her blouse in the kitchen with its mismatched dishes and dollars in the sugar bowl, her skirt in the bedroom, where Fanny’s mirror reflected crepey cleavage and flappy underarms, more like the Ma and Fanny of late than the young Fanny who’d once turned heads with feathered hats and hiked-up hemlines.

Fanny’s bedroom was carved mahogany, the bed an odd three-quarters size. Fanny had never married, but there’d been a man, a married man, Ruth knew, when Fanny had lived down on Essex Street, this bed perhaps just big enough for chance nights together in close embrace, yet small enough for Fanny alone. Later, she’d moved uptown, left the garment factories for a tailor shop where she’d hand-stitched lace on rich ladies’ underwear, seed pearls on satin wedding gowns. Ruth had always thought Fanny’s married man had somehow gotten her this better job, maybe payment for no wedding ring and going back to his wife.

Fanny’s toilet waters and powders lined the dresser, her favorite red lipsticks well-worn to the groove of her full lower lip. Her smell hung in the air, rosewater and Camels, the heady rush enough to make Ruth regret quitting in ’64. Fanny had smoked for seventy years. A cholera on the Surgeon General, she’d scoffed.

The closet summarized Fanny’s life in ladies’ soft goods, the way she’d made her living. Faded housedresses, old-lady suits, blouses missing buttons at the girth of bosom. Hidden behind, white shirtwaists, possibly from one of the factories where Fanny had toiled, and one lone flapper dress—chiffon the deep scarlet of Fanny’s lips, a silhouette designed for the narrow hips of a young woman who’d never borne a child.

On the closet shelf, black pocketbooks, with their wallets and change-purses and more treasures of cash. And on the floor, rows of black shoes, each stuffed with a pair of nylons. Under some of the nylons, jewelry—pearl earrings, a gold ring, a ruby-looking brooch Ruth had never seen her wear. As if the cash in the coat pockets up front was just a decoy for the casual thief.

Outside, it was too cold to snow, said the papers. Yet in Fanny’s bedroom, sweat dripped, from the work and also the weight of Fanny’s belongings, Fanny perhaps watching from somewhere overhead. Ruth peeled down her girdle—youthful memories of languid undressing in front of her husband Al now reduced to a daily tug of relief—and lay on Fanny’s bed in bra and panties, arms spread, like Jesus on the cross, or one of those snow angels she used to make when Ma wasn’t watching. Ma didn’t believe in angels any more than in Jesus. Maybe Fanny wouldn’t approve of snow angels on her bed, but if Ma was right, then Fanny wasn’t anywhere up there judging. Or else they were both up there, laughing at old-lady Ruth.

That’s when Ruth found the newspaper clippings in Fanny’s nightstand, under Fanny’s jar of Vaseline, as if directed from above. The face tells the secret, Fanny always said regarding her beloved Vaseline, the eighty-year-old cheek she’d offered for Ruth’s kiss as soft as that chiffon dress in her closet.

The articles showed datelines but no year. Essex Street meant before Fanny had moved uptown. Ruth remembered her mother spending the night in the city to help with that move, maybe the only night Ma ever slept away from Pop, possibly back to back against Fanny in this very bed. That would’ve been 1945, Al just back from the war and Ruth pregnant with Susan, because she remembered Ma brought home a baby gown, hand-smocked by Fanny, which Ma’d slipped to Ruth in private. Pop wouldn’t have allowed baby clothes before the baby on account of rules against tempting the evil eye.

Fanny wasn’t one for following rules nor for taking orders from men. In the factory, sure. But at home, no. Starting from when she was fifteen and packed a satchel to walk to Hamburg for the ship to America. Her father said, It’s a shande a girl can’t find a man to take her to America. A maydl her father had called her, a girl, and a shande, a shameful girl. Her father, who thanked God every morning in his prayers for not making him a woman. That’s when Fanny gave up being a girl for good.

In New York, she answered to herself, at least in her own apartment. Even with her married Max, she let him help with the rent, but she kept the key. He wanted to come, he had to knock on her door. It was her home, after all, her doilies, her fringes (girl maybe not for her, but girlie was okay). The furniture, on the other hand, heavy like a man’s to remind her she was staying put here in America, no more packing up in a satchel. With enough carved scrollwork, even a rich lady could feel at home.

A rich lady like Max’s wife, she should stay uptown where she belonged. A needy woman she was, always phoning, ever since Max had insisted to put a telephone in Fanny’s apartment. Max himself never phoned ahead. Just showed up or not, Fanny should be ready.

Last night, the phone was ringing as Fanny trudged up the stairs from work. “A plague on you!” Not at all ladylike. “Dershtikt zolst du vern.” You should be choked. “Derharger zolst du vern.” You should get killed. Not since her father had Fanny heard such language. So today, after Saturday half-day at the factory, she gets off the streetcar by the police station to make a report. Who says a lady can’t be dangerous just because she’s rich? Okay, maybe not dangerous dangerous, but if the police arrest her, maybe Max is finally free to make of Fanny an honest woman.

Not that Fanny needs the paper, or the rabbi, to prove what’s between her and Max. It’s enough how he talks to her. My shayna maydl, a whole different meaning from Pa. His voice hot and urgent when they’re in bed together, naked, Fanny doing for him something his wife would never do. She don’t keep herself up like you, his lips on her belly, then sliding down to what’s below.

But Fanny knows what makes Max’s wife soft in the middle. The one thing Fanny never gave him, children, flesh and blood. The boy, Jake, who helps Max with the business, chasing criminals who jump bail, strong-arming borrowers who don’t pay back. And the two girls, who stay home with the wife, learning to boss the maids. The wife, who maybe never takes off her white gloves, not even in bed.

So, the police station, and that farshtinkener detective, Donnelly, does he even listen? Never looking up from that form where he’s scratching, for all she knows a form for lost dogs, probably tossed into the trash the minute she’ll turn to go. “Mil-dred Katz,” she enunciates, and he’s looking up now with a wink and a nod, not at her but at the corner cops, crotchety Kelly and that kid Sweeney, slouching in for their shift. “And her son Jake,” she throws in, quick and loud, threats from a man more convincing? Then her own nod at Kelly and Sweeney and a shimmy of her backside in its thin summer skirt as she retreats to the door. Maybe they’ll keep an extra eye out for her after all.

Back at her apartment, Fanny lights a cigarette, inhales a spicy drag, then balances it on her gas burner while stripping off her blouse, filling a pan for a sponge bath, careful to keep away from the open window. Anyone across the street can see in, customers drinking beer at Feenie’s, tables out on the sidewalk in the summer swelter.

She fingers through her closet for something to please Max, pauses at the red dress, his favorite, never mind (or because?) the buttons no more close over her bosom. Then she irons a white blouse, sprinkles rosewater in her cleavage, and pins over that cleavage a pin Max once gave her, the one with the red stones, surely not rubies, but garnets maybe, or glass? Max will come tonight or he won’t.

Jacob Katz Gets 20 Years

for Killing Father in Family Row

March 20. Jacob Katz, 22 years old, pleaded guilty yesterday to second-degree murder in the killing of his father, Max Katz. Justice Stephen Callahan sentenced Katz to 20 years to life in Sing Sing Prison. In exchange for the guilty plea, all charges were dismissed against Katz’s mother, Mildred, who was present alongside her son at the shooting in the apartment of her husband’s long-time mistress, Fanny Siegel.

After the shooting, both Jacob and Mildred Katz claimed to be the shooter. Miss Siegel insisted the wife had fired the gun, but Max Katz declared he had been shot by his son before succumbing.

At the sentencing, Mildred Katz cried in court: “Don’t do this, Your Honor. It was me!”

Max shows up smelling of cologne and cigars, which means he took the wife to a restaurant, never mind the chicken leg Fanny stewed for him on her burner. Max is always hungry after one of his wife’s lousy meals, but a restaurant steak fills him up. If he’s had dessert and cognac, he might even fall asleep without getting what he came for. But Fanny knows how to rouse him. After all, what he came for is what she also wants.

Sure enough, tonight Max is snoring in the easy chair before even taking off his shoes. Just the night Fanny has planned to put her foot down about the wife and her threats. Last week Fanny warned Max she’d go to the police, but did he believe? Just pinched her bottom and said, Be a good girl. Again, with calling her maydl, never mind she knows better than to tell him her age. So that night she’d shut up about the police and let him undress her, slowly, with the lights on, the way he liked.

Tonight, it’s Fanny undressing Max, unlacing the shoes, unzipping the trousers. But when she gets him onto the bed and guides his hand under her blouse, his fingers stir. They are strong fingers, hands big enough to cup Fanny’s breasts, Fanny’s bottom, which they do now, squeezing, stroking. Then the rest of him stirs, against the place where Fanny also stirs, so she has to pull up her skirt and push aside her garter belt, fast, while Max wakes up enough to do the rest.

Afterwards, Fanny finishes undressing, shuts the light, and gets into bed beside him, never mind a nightgown. Max likes he should feel her skin, come morning. So that’s how the wife and the boy find them. Naked. Smelling of sweat, and more.

Except he’s barely a boy anymore—a plug of a man, with meaty shoulders and swarthy complexion, scary enough to do Max’s business, strong enough to knock down Fanny’s door. Afterwards the police will find a key ring in the hall, Max’s keys, which the wife must have lifted from his pocket thinking one would open Fanny’s door, ha!

The wife, you could almost mistake for a lady, still dressed from the restaurant in an evening dress, silk; Fanny knows her material. And sure enough white gloves up past her elbows. The two of them must’ve made a funny pair waiting at Feenie’s across the street, watching for the lights to go out, to catch Fanny and Max in the act. The wife wouldn’t know that, with Fanny, Max prefers the lights on.

All this Fanny will figure out later. Right now, there’s the splintering of the doorframe and the crack of gunshots, then the thud of the gun dropping, and Fanny groping for the lamp. Then Max’s blood, warm and thick, and the boy, not looking at his father, who he had maybe just shot, but at Fanny, who is torn between pressing the bedsheet to stop Max’s bleeding or wrapping that bloody sheet to cover her nakedness. Then the sirens and the shouting and the policemen pounding up the stairs.

And the wife and son not even trying to run, also not trying to help, maybe sticking around to make sure Max is dead. So, when the policemen storm in, Fanny points right away to the wife, who all these years she’s wished would drop dead, and says without a second thought, “It was her! She done it!”

Governor Grants Commutation

to Man Who Slew Father

March 22. Governor Harriman yesterday commuted the twenty-year sentence imposed on Jacob Katz for the killing of his father, Max Katz. The shooting took place ten years ago in the downtown apartment of Max Katz’s lover. After pleading guilty, Jacob Katz served half his sentence.

Katz was met by his mother at the prison gate. It was widely reported that Katz had pleaded guilty in order to protect someone else. He and his mother were both found in the mistress’s apartment at the time of the shooting.

“It was good of the governor to recognize he’s innocent,” Mrs. Katz said. Governor Harriman, however, tendered commutation, not pardon. Katz remains a convicted murderer.

The corner cops get there first, Kelly and that kid Sweeney with the long neck and the pimples. Max bleeding, and the cops shouting, and then somebody screaming. The wife? Or is it Fanny screaming? Then another sound. Groaning. Max groaning. Not the groan Fanny usually hears, likes to hear. Max bleeding, and nobody doing nothing except shouting and shoving.

Then it’s Kelly, with his hands on her waist. His sweaty hands, on her skin, and she realizes she’s still naked. And what about the wife? Fanny, in her own apartment, Max bleeding on her bed, and they won’t let her near. The wife, her white gloves now red with blood, ha, ruined—her they’re letting near? Is that her holding Max’s hand?

“She done it!” Now Fanny is screaming, if just to get Max’s attention, his eyes closed, then open. “She killed him!”

A curse, her father would say, what with Max not dead, at least not dead yet. His eyes searching. For me, Fanny thinks, straining against goddamn Kelly’s strong hands, he got nothing better to do but hold onto a naked woman?

So, who’s close enough for Max to look? The wife. Then, shouldering in, the son, Max’s Jake. The three of them, a triangle, a family. Max, with his heavy-lidded eyes on the wife, the boy, the wife.

“It was him.” A rasp of a voice, is that Max? Max never whispers. It was him. Or did he say, It was her?

Then blood gurgles from his lips, those lips that just minutes ago were on Fanny’s lips, and more. Now his eyes close, stay closed, no more talking, no more.

It must have been the kid Sweeney who handed over her wrapper from its hook. Then here comes Donnelly from this afternoon. She pulls tight the belt around her waist. That lousy detective, all this is his fault! Never mind Fanny and what her father would say was a curse, her curse, if Max dies, if Max is dead.

If Max is dead. Donnelly got here from the station faster than the ambulance? Did anyone even call an ambulance? “What the hell happened?” Donnelly hollers. “And how come I don’t see cuffs on nobody?”

Then Kelly is looking at Sweeney, and Sweeney’s pulling out handcuffs, standing, looking, pimples blushing red as Max’s blood. So, it’s Kelly grabs the cuffs and slaps them on Jake. “He done it.” Kelly points at Jake. “The dead guy said so.”

The dead guy. Tighter, tighter Fanny pulls her belt, as if to hold herself in.

“You’re sure he said the boy?” Donnelly demands. “He called him by name?” Donnelly’s red now too, near apoplectic to have missed it.

So Kelly says, “Sure he said his name. The boy. James, ain’t it so?”

Freed Murderer Shot Dead

Jan. 23. Jacob Katz, owner of Katz’s Garage on East Seventy-first Street, was shot dead yesterday at the garage he has owned since his release from prison after serving ten years for killing his father.

Katz’s guilty plea in the killing of his father has always been under a cloud of suspicion. Max Katz was shot dead in the bed of his mistress, who blamed the wife, Mildred Katz, for the shooting. But the son, the only other person in the apartment, witness or perpetrator, pleaded guilty and went to prison for the crime.

Jacob Katz’s body was found by his mother and possible accomplice, who told the police, “I blame that woman.” It is unknown if she was casting blame for the death of her husband or her son.

Fanny never knew the son was getting out of prison until she read it in the newspaper. You think they told her, that stinking Donnelly and his crew? As if she was nobody. While that murdering snake of a son got to prowl the streets a free man, go home to supper with his mother, own a business even, a supposedly legit business.

Except wasn’t it his mother—the wife—who killed Max? After all these years of saying so, Fanny could’ve sworn it was true. She could see the wife with the gun in her hands, in those ridiculous white gloves like she just came from the opera.

Of course, it had been dark, Fanny and Max asleep like they were. But the white gloves you could see, the streetlamp blazing through the window. Although wouldn’t the streetlamp have shined also on their bodies, her and Max in the bed, two pale naked bodies? Who would the wife have been aiming at? Fanny she hated for sure. But with Max dead, it’s not only revenge the wife got but also money.

Plenty of money, Max left it all to her in his will. The business would’ve gone to the son, although not the kind of business you’d mention in legal papers. What were the daughters, anyway, just someone to marry off? But the son Max never shut up about, Jake this, Jake that. So how come Max fingered the son? Wasn’t he asleep, snoring, what could he have seen? Then Fanny screamed the wife done it, and the wife also screamed she done it. But Max says it’s the boy, and then he dies. Now the boy dead, too—let the wife and those girls sit alone counting whatever’s left of Max’s money.

Max loved Fanny, in his way, bringing her flowers and chocolates and the occasional piece of jewelry, not the crown jewels but nice enough. He squired her about the neighborhood, never ashamed to be seen with her at Feenie’s across the street. And after buying her dinner, he let her do for his body, but also he did for hers.

Didn’t he promise her he’d leave the wife, just waiting for the boy to grow up, then the girls? He hated his wife, this he swore to Fanny. On the other hand, if Fanny thought about the lies he told to the wife; then also she’d have to think about the lies he’d told to her. In the end, it was the boy Max sent to jail. The wife, with his last dying breath, he saved. So, who did he really love?

Katz, Mildred. Mildred Katz, beloved wife of the late Max Katz, cherished mother of Bess (Seymour) Shapiro of Rockaway, New York, Clara (Howard) Brodky of Cleveland, Ohio, and the late Jacob Katz, died in her sleep last night at the age of ninety-one. Mrs. Katz was a loving wife, mother, grandmother, and patron of the arts. Funeral service at noon today at Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue.

Like Ma, Ruth didn’t much believe in heaven, but if Ma and Fanny were together again, somewhere, surely they were sharing a last laugh about Max and the newspaper’s so-called beloved wife.

Fanny had managed one last visit before Ma died, on the bus to South Orange, then another bus to the hospital. Ruth couldn’t pick her up, because she never phoned to announce she was coming. Fanny just showed up, her lips still red, except for the deep creases where lipstick could no longer reach, her hair still raven, except for the roots. She pulled up a chair next to the bed, close as could be, holding Ma’s hand entwined with her own, so Ruth couldn’t tell one bony finger from another.

After, Ma couldn’t stop talking about her. How Fanny came first on the boat, then taught Ma how to ride the streetcar, to light the gas oven, to talk “American.” How Fanny, not Pop, used to bring Ma chocolates, never mind probably bought by the married man. Always the married man, never a name.

And Fanny’s almost-baby. Ma told about Fanny’s almost-baby as if she forgot Ruth already knew, had helped with the money for the so-called doctor, had been already a married lady herself, her Al off fighting the war.

“He promised he’d marry her,” Ma said now, as if no time had passed.

“Fanny’s married man?”

“Who else?” Ma pushed away the water Ruth offered, with strength Ruth didn’t know she still possessed. Was Ma angry? Or else why would this be practically the last thing she’d ever talk about?

“Maybe he would have married her,” Ruth said, “if she’d given him a baby.”

“Oh, Ruthaleh, still you don’t learn?” Ma said. “It don’t cost nothing to promise love.”

So, it wasn’t Fanny that Ma was angry at, of course, but the married man, Max, the dead man. Although that Ma never mentioned, mayhem and murder.

Murder Ma left for Ruth to discover, too late, after everyone she might ask about it was gone. Two murders, in fact. One, Fanny knew who did it, if you could believe the clippings. And the other, Fanny didn’t know… or she didn’t say, at least not to the newspapers.

Even at the end, with no time left and Ruth practically an old lady herself, there were secrets Ma kept between herself and Fanny.

Ruth tucked Fanny’s newspaper clippings into her own pocketbook, plus nearly five hundred dollars of Fanny’s cash, hidden under the weight of Fanny’s keys. Lucky she’d had those, which Fanny had given to Ma years ago, just in case. Fanny’s purse, with its own set of keys, had never been found after the cops picked her up off the pavement. Somebody was right now probably trying out Fanny’s red lipstick, smoking Fanny’s Camels.

With all the smoke Ruth had been breathing in Fanny’s apartment, how much more could a real cigarette hurt? She threw on her skirt, her blouse, listened to the wind howling outside Fanny’s windows, grabbed one of Fanny’s heavy coats near the door, and set out in search of cigarettes. Not Fanny’s Camels, it was the smooth taste of Marlboros Ruth still craved, all these years since the Surgeon General. She buttoned up the coat, shoved her hands into the pockets, her breath curling in front of her face as if she already held a smoke between her lips.

The voices on the street spoke Spanish. The corner store, when she got there, sold cigarettes along with chili peppers and pinto beans. The counterman rang up sales for lottery tickets and flirted with girls buying chocolate bars, tins of Midol, Spanish-language newspapers. Ruth tried to imagine Fanny in this place, in her same black coat now skimming Ruth’s calves, on Fanny probably down to her ankles.

When the counterman nodded toward Ruth, she pulled her hand out of Fanny’s coat pocket with enough coins and crumpled dollars to pay for the Marlboros, one last gift from Fanny. And something else came out, too, a slip of paper with Ruth’s name—Ruty, in Fanny’s wiry scrawl—and her telephone number in New Jersey.

Ruth had found papers like this back at Fanny’s apartment, alongside all that cash in the pockets and pocketbooks, wallets and change purses. Everywhere, scraps of paper with Ruth’s name and telephone number, Fanny shouldn’t forget. Especially now, with Ma gone, who else could Fanny count on?

About the Author

Elizabeth Edelglass is a Connecticut writer whose fiction has recently appeared in New Haven Review, Tablet, Lilith, JewishFiction.Net, and three recent anthologies, including Best Short Stories from The Saturday Evening Post Great American Fiction Contest 2017. A past winner of an artist fellowship from the Connecticut Commission on the Arts, she lives in the New Haven area, where she is at work on two novels, short stories, and poetry.