When I was in college, my favorite aunt died. I had seen her only a few months before, and now she was gone. My grandmother went just a few months later. I learned this standing at the rotary pay phone, also now gone.

I returned for a high school reunion a few years ago. When I drove by my old house, the split-level with the big picture window in the front was there, but it was painted differently, the crab apple tree and the bushes gone. My house was gone.

Danny’s always had the best pizza in town. It was still there. And Danny was still there although much older. But it wasn’t the same. Gentrified, it too was gone.

Loss can be a terrible thing but not always. In some cases, “gone” is good. After all, absence makes the heart grow fonder. People who lose weight are happy.

But it’s not only what we lose that changes us. It’s what we keep as well.

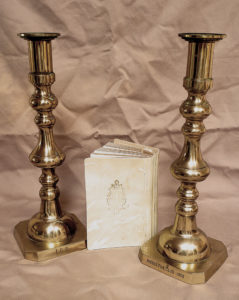

When I returned home after my aunt’s death, my mother gave me my aunt’s bible, its pages well-worn with use. Holding it in my hands, I felt her presence as if she were not gone. When my mother died years later, I found she had kept my aunt’s candlesticks. I use them almost every week and find they bring light into a world filled with darkness.

The candlesticks are tall and made of brass. My aunt’s name is engraved on them along with the year 1959 and the name G. Fox and Company, where my aunt worked. Founded in 1847 in Hartford, Connecticut, the company treated its employees well and fostered fierce loyalty. Not surprising since employee benefits included in-store hospitals, loans, and at-cost meals. The company isn’t around anymore, and neither are those kinds of benefits.

The candlesticks honored my aunt’s twenty-five years of service as a comptometer operator, an occupation that is gone (the name comptometer sounds very important, but we would call it an adding machine). They stopped manufacturing comptometers around the time she died.

I have a box of photographs my parents kept of my aunt. Sometimes I open it and spill the photos across the kitchen table. Almost everyone in them is now gone as well. The past does not often open as easily as that box.

But the past opens up to us in other ways. Consider Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. A flood of memories is triggered as the narrator dips his madeleine into his tea. Such vivid, involuntary sense memories strike all of us. A bite of a hamburger reminds you of that special Fourth of July at the seashore. The smell of roses of the day you planted them, kneeling beside your mother in the garden.

But there is a more subtle way we remember loss, and it is through what we have become. When I sing, I know that voice comes from my grandmother. When I run, I know my athleticism comes from my father. That genealogy has become the second most popular hobby in America is no surprise. The desire to discover who came before us stems from a great need to connect with those who are gone and to understand those parts of ourselves that remain. The habits, quirks, and talents we have.

In Judaism and much of Christianity, an eternal light or altar lamp remains lit in the house of worship. Tradition says they remind us of the Divine presence. But there are other presences that we remember every moment of every second of every day, through things and people we no longer have and as the people we have become.

We are eternal lights too.

I finally saw my grandmother’s grave just a few years ago. I stood there and cried for the memories we had shared, all I had lost, and all I had become thanks to her.

I still have not seen my aunt’s grave marker. Perhaps it is time.

Mara Fein has been published most recently in The Tahoma Review. She holds a PhD in English from the University of Southern California and lives in Los Angeles, but her best memories reside in Hartford.