By Beth D. Man

“Why am I sad? Oh! lonely ever / Mourn I all afar from me / The foreign land is fair, but never / like my pleasant home can be.”1 This lonely verse is part of a poem titled “A Song of Home,” by Sarah Tabor. She wrote it on board the Alice Frazier, a whaling ship, in 1841.2 The mid-nineteenth century was a time of opposing realities for men and women. For men, it was a time of exploration and freedom. For women, it was a time of constraint and obliteration. Perhaps, nowhere else was this dichotomy more prevalent than in the lives of husbands and wives involved in the whaling industry.

Whaling was a man’s world, a world of glory and achievement. There was nothing glorious about whaling for women. They were not allowed on board as part of the crew and certainly not as a captain. Excepting extreme emergencies or rare instances of disguised gender, women on whaling ships only participated in subservient roles: prostitute, captain’s wife, or captain’s daughter. Daughters were not permitted to be participate in the running of the ship once they reached teenage years, and captains’ wives needed their husbands’ permission to assist.3

Captains’ wives often boarded whaling ships with their husbands, not to promote their own self-interest, to explore the world, to meet new peoples, or to make new discoveries; they left their homes to prevent their husbands from engaging in debauchery. According to historian Marjorie Kaufman, “Whale ships had wild reputations as floating castles of prostitution and whaling captains were quite flamboyant characters. Venereal disease was common.”4 Other reasons for ship travel varied “from keeping their men from the demon grog… to spread[ing] the Christian word or, for the most part, because they didn’t want to be separated for years from their menfolk.”5 Women were willing to embark on those long journeys for the aforementioned moral reasons or for love, but also because life on land did not offer them anything better.

Mrs. Tinkham’s cabin, and the story it tells, gives testimony to one whaling wife’s brief but harrowing ordeal of obedience and misery. In 1875, John M. Tinkham, age thirty-six, was captain of the Charles W. Morgan. It was one of the finest whaling ships of its age, and thanks to the painstakingly detailed restoration work on behalf of Mystic Seaport: The Museum of America and the Sea, the Morgan continues as a working classroom, giving today’s students a glimpse into what whaling life was like. The ship was built in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1841, at the dawn of a whaling economy that fueled the growing nation and westward expansion of the United States.6

Life on board a whaling ship for captains’ wives was not easy. Women had no duties and were not allowed to fraternize with the crew. Other than being allowed to yell, “There she blows!” if they’d spotted a whale, women could not participate in whaling activities.7 Most whaling wives spent their days at sea washing clothes, sewing, educating their children if they had them, writing in diaries, or reading.8 For any woman, this life would have been very isolating and lonely, but for Clara Tinkham, it was especially grueling. Not only did she have to endure the monotony and tedium of women’s work aboard ship, she was terribly seasick, and the illness did not relent. Wives usually stayed in the captain’s quarters with their husbands, but for Mrs. Tinkham, being confined below deck only exacerbated her distress. In hopes of alleviating her discomfort, the captain had a small cabin built for her on the deck of the ship. It was just large enough for a small bed and close enough to the side of the deck so that when the need arose, she could run to it for relief.9

Mrs. Tinkham withstood her seasickness for a year and a half, before returning to land permanently.10 According to a woman claiming to be a descendent of the Tinkhams, Nan B. Jackson, “She did not finish the voyage but sailed from the island of St. Helena to England where she eventually took a ship back to the States. Back in New Bedford, she had the first of seven children. Captain Tinkham did not return to the sea after this voyage but had a farm along the Acushnet River where later a street was named after the family.”11 Fame and admiration followed Captain Tinkham’s career. Unfortunately, for Mrs. Tinkham, all that is left of her is the little cabin in her name on deck of the Charles W. Morgan.

For the uninitiated, life on board whaling ships like the Charles Morgan may have been thought of as luxurious living. “The merchant wives had large magnificent staterooms on board, wore elaborate clothing and carried exotic provisions.”12 This sentiment, however, was far from the realities of scurvy, fleas, cockroaches, and mutinies.13

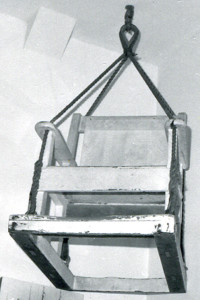

The only reprieve whaling wives may have experienced was the occasional gamming session. When whaling boats met at sea, the crew members would socialize, but if the ships were “hen friggets,” meaning there were wives on board, one woman would be hoisted over to a whaling boat in a “gamming chair” to board the other’s ship. The gamming chair was specifically designed for the purpose of allowing whaling wives to spend time together. According to the New Bedford Whaling Museum, “Gamming was a diversion for a wife, as well as the captain and crew. The captain’s wife was lowered from ship to whaleboat in a gamming chair and rowed to the other ship for a festive social occasion, visiting with the other captain’s wife.”14

Were these sessions truly festive? We will never know, as the wives’ conversations were not recorded. But given how terribly difficult it must have been for the women to live among an all-male crew, at sea for months on end, far from friends and family, it’s hard to imagine their visits as completely festive occasions. It’s clear from Sarah Tabor’s poem and Joanie DiMartino’s poem “Mrs. Tinkham’s Cabin” that these sister sailors had terrible laments, though they may not have been able to express them during their very public gamming sessions. It is likely that the “hens” felt obligated to uphold their stoic obedience and dedication to their role as dutiful wives, and as such, appearances may have required them to be festive. Their true voices were unheard for decades. Today, “Mrs. Tinkham’s Cabin” has opened our ears and our hearts to finally give these sister sailors the appreciation they deserve.

References

1. Sarah Tabor, Alice Frazer’s Captain’s Log Entry, 1851, “A Song of Home,” The Mariner’s Museum and Park, accessed November 29, 2016, https://www.marinersmuseum.org/sites/micro/women/goingtosea/wives.htm.

2. Ibid.

3. “Women in Maritime History – San Francisco Maritime National Historic Park,” National Park Service, accessed January 31, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/safr/learn/historyculture/maritimewomenhistory.htm.

4. Marjorie Kaufman, “A Tap on Shoulder From Whaling Days,” The New York Times, March 5, 1995, accessed November 29, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/1995/03/05/nyregion/a-tap-on-shoulder-from-whaling-days.html?pagewanted=all.

5. Ibid.

6. “Charles W. Morgan,” Mystic Seaport, Accessed December 20, 2016, http://www.mysticseaport.org/explore/morgan/.

7. “Life Aboard,” New Bedford Whaling Museum, accessed November 29, 2016, https://www.whalingmuseum.org/learn/research-topics/overview-of-north-american-whaling/life-aboard.

8. Ibid.

9.”Lecture: Tour of the Charles W. Morgan Under Restoration,” Mystic Seaport, accessed December 23, 2016, http://educators.mysticseaport.org/scholars/lectures/morgan_tour/.

10. Ibid.

11. Nan B. Jackson, blog post, the website of Mystic Seaport, April 1, 2014 [7:56 AM], accessed November 29, 2016, http://www.mysticseaport.org/morganblog/questions/.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.