What is the benefit of the wide proclamation as opposed to the slow reveal?

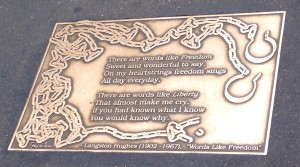

Tributes to literature in two different cities help to answer this question. In mid-Manhattan, the Library Way showcases metal relief plaques sunk into the ground; it is a best-of quote series that was donated by the Grand Central Partnership and other organizations in 1998.1

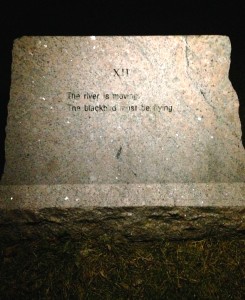

Hartford, Connecticut has its own word walk, but its location does not engage as much foot traffic. It sits by the side of the road and is not immediately attributable. Walking alongside the tombstone-shaped marble, one notices the striking words:

He rode over Connecticut

In a glass coach.

Once, a fear pierced him,

In that he mistook

The shadow of his equipage

For blackbirds.

No author is named. A few yards beyond lies the next stone:

The river is moving.

The blackbird must be flying.

One comes to notice more and more carved marble stones, all some distance apart. And upon further investigation, one realizes the stones contain lines from Wallace Stevens’s poetry. He often composed poems as he walked to and from his job at a local insurance company, today known as The Hartford. The markers dot the two-mile walk from his workplace to his exurban home at Westerly Terrace in Hartford. He seems to have lived a quiet life on a peaceful street and counted among his pleasures his wine cellar. Perhaps the unassuming nature of his life is reflected in the subdued presentation of the stones.3

It is possible that the arrangement of these stones simply reflects how Hartford celebrates its literary heroes.3 Hartford does not always call a great deal of attention to its historically significant assets. For instance, the publicity about the former home of Mark Twain is relatively subdued. This seems slightly unfitting, as Twain himself was a public relations genius and an extroverted showboat.

It is possible that the arrangement of these stones simply reflects how Hartford celebrates its literary heroes.3 Hartford does not always call a great deal of attention to its historically significant assets. For instance, the publicity about the former home of Mark Twain is relatively subdued. This seems slightly unfitting, as Twain himself was a public relations genius and an extroverted showboat.

Unlike New York City’s Library Way, which was made possible by a team of large, public organizations, the Wallace Stevens Walk was funded only by The Hartford and developed by a small, private alliance. That alliance is the Friends and Enemies of Wallace Stevens, a few individuals who in their very name address the struggle of understanding modern poetry. According to their website, one is only an enemy of Stevens’s poetry until gaining enough familiarity with it; appreciation comes gradually.4 The Wallace Stevens Walk’s presentation of simple and unlabeled poetry forces one to engage with the language directly. Coming into contact with these unattributed lines causes one to focus on the nature of the words. The walk surprises pedestrians and provides them with an unexpected opportunity to familiarize themselves with Stevens’s poetry. For those who find their interest piqued, a Google search of the lines could help place the poem into a wider context.

If the Library Walk invites one to quickly ingest a few words or peruse great works in the Schwarzman building, then the Wallace Stevens Walk invites one to thoroughly reflect upon a single poem and learn more about one piece of our cultural heritage.

Regardless of presentation, these walks both celebrate good writing and use it to better our paths.

Works Cited

1. “Library Way,” Grand Central Partnership, accessed January 25, 2016. http://www.grandcentralpartnership.nyc/our-neighborhood/library-way

2. Jeff Gordinier, “For Wallace Stevens, Hartford as Muse,” New York Times, February 23, 2012, accessed January 19, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/26/travel/for-the-poet-wallace-stevens-hartford-was-an-unlikely-muse.html

3. ibid

4. “The Wallace Stevens Walk,” Friends and Enemies of Wallace Stevens, accessed January 19, 2016. http://www.stevenspoetry.org/stevenswalk.htm

Carolyn Bernier

Managing Editor