By Con Chapman

It is not my intention, I assure you, to bore you with a tale of our Founding Fathers, who are regularly invoked by moralists here in Virginia and elsewhere in this great land of ours to convey hortatory lessons to the young. The tale of how Washington once threw a silver dollar across the Potomac is traditionally recounted to impressionable youth, for example, when it seems to me nothing more than an example of the spendthrift habits of the city that nowadays bears his name.

No, I mean to set down for my own benefit an account of an unusual case that came my way a few years back, since the matter was disposed of without the intervention of a court or even so much as a letter or a memo to my files. Still, it was the most lurid—is that the right word?—situation I’ve ever been involved in on behalf of a client, and so I feel I should create a record of the events that upset my sleepy little practice here in Williamsburg, where history hangs heavy in the air.

I should admit before proceeding any further that it wouldn’t take much to disturb my work as a sole practitioner, a one-man law firm that I am allowing to slowly expire like an inflatable beach raft at the end of the summer as I glide softly toward retirement. It’s just that nothing ever does. Day after day, the same old thing: wills and trusts, a minor conveyance of land, a nasty letter to a painting company that didn’t finish a job. Such are the tasks I perform these days for the few clients I allow to disturb my amateur poeticizing; I don’t have the stamina of a Faulkner, so I string together pretty words into macramé-like verse that I send off to little magazines with less optimism than Lenore, my office manager (she’d prefer it if you didn’t refer to her as a secretary), feels when she buys a lottery ticket.

Still, the ennui of my days makes me an easy prey when something new and different, as my father might say, walks in the door outside of which hangs a humble shingle bearing the strange device “J. Carter Reed, Attorney.” Lenore asks me annually or so why I don’t suffix “Esquire,” a title to which she thinks I’m entitled, to my name.

“Because it’s an honorific,” I say.

“What does that mean?”

“That it’s something others say of you. It’s tacky to apply it to yourself.”

“All the other lawyers do it.”

“If all the other lawyers in Williamsburg jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge . . .”

“I know, somebody’d accuse you of pushing them.”

We’d put this particular patter behind us for the year a few months back, however, so when she spoke to me on the morning in question, it was on business.

“There’s a lady outside who doesn’t have an appointment,” Lenore said as she poked her head into my little office, which differed from the reception area in which her desk was located only by the addition—or is it subtraction?—of a window. If she had her way, that aperture would be stopped up with a room air conditioner, but then—I told her—we wouldn’t be able to smell the magnolias in the spring.

“She doesn’t need one,” I said, a truth that went—for those who knew me—without saying. “What’s her name?”

Lenore looked down at a slip of paper on which she’d written a name as a mnemonic device to aid her after she’d walked the ten steps from her desk to mine. “Lunt,” she said. “Christine Lunt.”

“Send her in.”

Lenore disappeared and then returned with a slender woman in a reserved brown suit, the sort of outfit you’d expect to see on a British marquess out for a day of grouse hunting. She looked like a model, not because she was pretty—I would have called her handsome–but because she had the high cheekbones, perfect complexion and pissy look that seem to be a prerequisite if you’re going to patrol the catwalk or adorn the pages of a fashion magazine these days. Why that is I doubt I’ll ever figure out.

“Pleased to meet you,” I said, and she returned my greeting with what I assumed passed for a smile among her people: a thin little wrinkle of her lips, which bore a dark red color.

“Likewise.”

She declined my offer of something to drink; Lenore scooted out the door without unseemly haste, and we began to palaver.

“What can I do for you?” I asked after the pleasantries had been dispensed with.

“You handle divorces?” she said, more a statement than a question.

“Yes.”

“And restraining orders?”

I hesitated for a moment. “Yes—-those are often an unfortunate accessory that must sometimes be added to my toolkit.”

“How about . . . criminal law?”

I took stock of my personal situation before responding: just past sixty years old; good health, although I fainted last Christmas when I stood up quickly after an evening of too much red wine; reasonably sure I could retire in five or six years; and determined not to blow it by getting in over my head.

“I have, but—like Bartleby . . .”

“Who’s Bartleby?”

“A scrivener in a Melville short story.”

“Never read it.”

“Anyway, like Bartleby—I’d prefer not to practice criminal law. Are you—in some sort of trouble?”

“I’m not, but I may have to report someone to the police.” She paused. “My husband.”

I inhaled and let the air out more slowly than was my custom. “Why don’t I let you . . . just talk for awhile and tell me all about it?”

“Fine,” she said. I got the impression she’d never used the expression “Okay” before.

“I’m an F.F.V.,” she began, “and so is my husband—Dalton.”

It was a good thing—for once—that my mother’d been haunted by a sense of lost gentility all her life, since otherwise, I wouldn’t have known that the initials my prospective client had just rattled off, as if it were the upscale brand of her purse, stood for “first families of Virginia.” It was my mother’s wish, throughout her long, smoke-filled life, that she would one day be inducted into that dubious society, whose members had the right (in her mind) to lord it over the common rabble. Alas, Dad’s little dress shop never threw off enough free cash to pay for the services of a genealogist, without whose blessing Mom’s prospects were doomed, since her limited academic skills, honed to a fine edge at Miss Finch’s Secretarial Academy in the third decade of the twentieth century, were no match for the bureaucratic indifference she faced at the registrars of probate and deeds where the vital records so, er, vital to her task were kept.

“That’s—quite a distinction,” I said, and I tried to quash the dubious air that sometimes creeps into my voice when I flatter the pretensions of prospective clients.

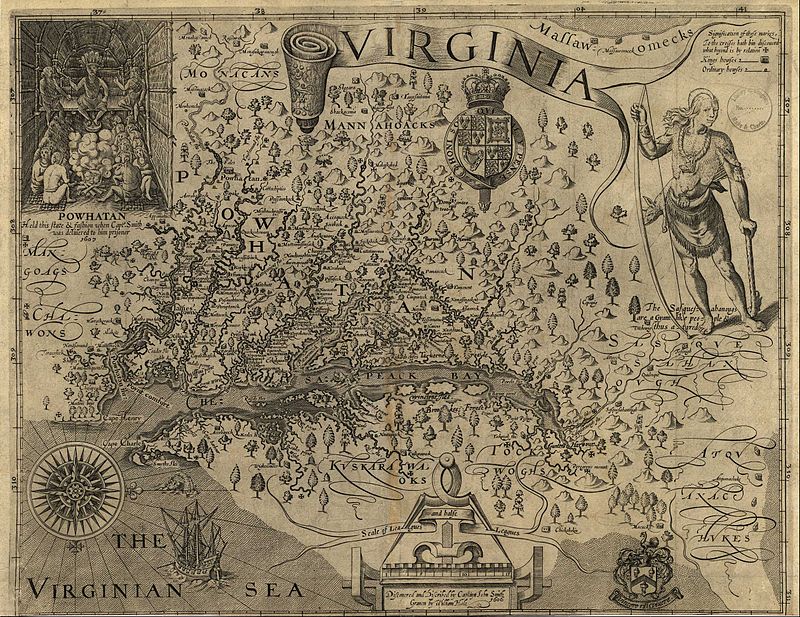

“As such, we both go way back,” Christine said. “In his case, all the way to the first settlement at Jamestown.”

“Goodness!” I exclaimed with as much sincerity as I could muster.

“Dalton’s ancestors were alive during the Starving Time—have you heard that phrase before?”

In fact, I had—I got a B+ in Virginia History, a course required of all students as a condition of graduation from high school in our state.

“Yes. It must have been terrible.”

“Dalton’s great-great whatever father survived. His great-great whatever mother did not.”

I wondered if I should express the customary “I’m sorry to hear that,” but I figured that, since four centuries had passed, the pain of the loss had probably subsided.

“It always amazes me what hardships those people went through. We really have no idea today with all of our comforts, and . . .” I went on blandly like this for a few moments more; then she interrupted me.

“She was murdered by her husband.”

“Oh.”

“While she was pregnant.”

I gulped, audibly I suppose, for Mrs. Lunt’s face took on an air of satisfaction like that of a cat who’s killed a chipmunk, she had shocked me with her revelation. “I see,” was all I could say.

“Those were, as you say, tough times,” she said. “People were starving. They ate their horses; then they began to eat dogs and cats, then rats and mice. They ate their boots and shoes and anything else made of leather. When that ran out, they began to dig up their dead and eat the corpses.”

My glibness deserted me at this point. “That’s . . . awful.”

“It’s all in the account by George Percy, one of the gentlemen who came to Virginia thinking it would be a land of plenty. I’m not sure it wasn’t even worse than he said, since he was trying to defend himself from blame for the things that happened on his watch.”

“I’ve never heard of anything so horrible,” I said in hushed tone like a prayer for the dead.

“You haven’t heard it all yet,” she continued. “Like I say, the first American male in the line killed his wife, while she was pregnant. He tore the fetus from the womb and threw it into the ocean; then he began to salt the meat of his wife—and ate her.”

“Good Lord.”

“The Good Lord was a little too late. By the time Percy was discovered, he’d eaten a good part of her. When other settlers arrived on the scene and discovered him, he denied everything. It was only after he’d hung by his thumbs—with weights on his feet—for a quarter of an hour that he confessed.”

The good old days, when the hearts of gendarmes were free to enhance their interrogations with techniques both creative and effective. “Did you . . . know any of this when you married him?”

“No. My interest was piqued when an old biddy gave a talk at an FFV soiree we went to and happened to mention that the baby survived and that its name was Dalton Lunt.”

This was, as you might surmise, a red-letter day in my lawyer’s diary. I wanted no part of the woman and her case, whatever it was, but I couldn’t bring myself to stand up and politely decline to represent her. I was gripped with a morbid fascination. I felt my lower lip move up and down, as it used to do when I’d stammer through an answer in grade school. After a moment, I regained the power of speech.

“So—what does all that have to do with you?”

“Dalton has said he wants a divorce,” she said coldly. “There’s apparently a younger woman in the picture.”

“Well, a divorce is typically a simple matter, if sometimes acrimonious.”

“It won’t be simple, and it will be acrimonious.”

“Why is that?”

“Because everything’s in my name. You remember the commercial real estate downturn of the late eighties?”

“Yes?”

“The fallout from that for Dalton was he had people chasing him for years on his personal guaranties. When he finally settled the last case, we decided to shield everything in case it ever happened again.”

“Oh. That was good planning.”

“We were in love then,” she said. Her voice cracked a little, and it may have just been her eyeliner, but I thought I saw a tear in her eye. “And we hoped to have children. I was damned if I was going to have their college tuition wiped out over some crappy condo deal.”

“So, you have him over a barrel, huh?”

“Yes, although sometimes I wish I didn’t.”

“Why’s that?”

She looked over my shoulder out the window. There was a greensward down below, with sidewalks crossing it, people passing by; some idly, some busily. My guess was she would have traded places with any of them without knowing more than she could detect from a second-story view.

“I think . . . I know . . . that Dalton has more than a little of his ancestors’ blood in him.”

I started, not sure where she was going. “What do you mean?”

It was her turn to exhale now, and once she had the wind back in her sails, she began again. “That first incident was in the 1600s. There was another in the 1800s. The Lunt male in that case was a doctor who was treating his wife for ‘nervous exhaustion’—a vague term that covered a lot of symptoms. She disappeared from society right before the beginning of the holiday party season, and her friends began to ask about her. ‘Not doing so well,’ he’d say, or ‘She needs more rest.’ Soon he wasn’t going out except at night, so he wouldn’t have to answer people’s questions. No one saw her all winter long—he kept up his medical practice, but one day in the spring, his assistant came to the house because there were patients in the office with appointments who needed to be treated—and he hadn’t shown up.”

“So—what happened?”

“When there was no response to the knocker, the assistant contacted the police. They came and broke down the door, and they found the doctor and his wife in a sort of basement laboratory—dead.”

“God.”

“His body wasn’t too far gone—he’d only been dead a few days. But hers . . .”

Here she paused. Up to this point she’d been relatively composed, almost forcefully so. Now . . .

“Excuse me, is there a restroom in your office, or do I need to go back out in the hall?”

“There’s one on the far side of the reception area,” I said as I stood up to show her the way.

She was gone for five minutes or so, and when she returned, she was noticeably paler.

“Do you want to continue your story?” I asked.

“No, I think you can probably guess what the police found. Anyway, here I am, another two hundred years later, in conflict with my husband, who wants what I have.”

“Is an equitable split of the property . . . out of the question?”

“I raised the possibility. He says he’ll give me the house, but he wants the business properties back.”

“It’s not really up to him.”

“I know that,” she said, looking down at her hands folded in her lap like a school girl on an unaccustomed visit to the principal’s office. “But you don’t know him. There are too many opportunities between now and . . . whenever we break up for him to do me harm.”

“Are you still . . . living together?”

“He’s in and out of the house. We have children, and we have to see each other for their sake, if only to hand them off for vacations and private school. We have a very big house on a two-acre lot. Nobody would hear me if he caught me there alone and . . . did something to me.”

I began to see the difficulty she was in. “Do you think you could get him to come to my office?”

“Alone or with me?”

“I don’t think it matters.”

“He’s a very busy man.”

“He also has no leverage.”

“What do you mean?”

“In order to get his property back, he’d have to explain to a judge how you ended up with it. ‘I was trying to hide my assets from my creditors’ doesn’t exactly make you a sympathetic figure.”

She emitted a little half-snort and looked relieved for the first time since she’d walked through my door.

“I’ll try.”

As we both expected, it took some time for her to persuade her husband to meet with me, which was fine because I needed to do some research. I looked into the history of Jamestown and traced the Lunt family back as far as I could. It turned out I wasn’t the only one digging, although someone else was engaged in the more literal kind.

An archaeologist had been working the colonial site in search of cannibalism for twenty years, lured by the account of George Percy that Christine had mentioned as well as five others. All agreed that the settlers there had dug up corpses and eaten them, a taboo in every society known to man—if there was a curse on their descendants, they deserved it. It’s not the job of science to confirm the supernatural, but the fact that there was more than one witness to the horrid state to which Jamestown had descended would have been enough for me. By the time I tracked the archaeologist down, he had made a discovery of a grimmer sort: the skull of a young girl, estimated to have been around the age of fourteen when she died, found in a trash pit along with the discarded carcasses of dogs and horses slaughtered for food in those desperate days. He gave her the name “Jane” and tested her skeleton to see if it had high levels of lead like the remains of upper-class members of the colony; the wealthier settlers ate from pewter plates, slowly poisoning themselves by doing so. Jane suffered from no such taint; the gentry of Jamestown had apparently decided, when the larder was bare and there were no lesser animals left, to eat one of their servants.

Next, I looked into the Lunts. I found a newspaper account of the nineteenth-century murder Christine alluded to and a few incidents that, while questionable, resulted in no legal action against Dalton’s forbears. After one late night of research, Lenore found me asleep at my desk.

“You’re taking this one too seriously,” she said. “Did you even get a retainer?”

“I suppose I should. Can you do up an engagement letter?”

“No problem.”

“I wish you wouldn’t say that.”

“Why not?”

“It makes you sound like one of those Goth girls with a nose ring at the coffee shop downstairs.”

“What’s the matter with it?”

“I know it’s not a problem. It shouldn’t be a problem for you to do the work you’re paid to do.”

“Somebody got up on the wrong side of the desk this morning,” she said as wandered off to make coffee.

When the day for my meeting with Dalton and Christine came, I was as ready as I would ever be. I knew enough about him to have figured out where his weak spot might be. He was sitting precariously atop a pile that his ancestors had stacked high, but there wasn’t enough swag in his bloodlines to support the life he apparently wanted to live; membership in the right clubs, the expensive but reserved luxury car, the attractive, high-toned wife. All that was costly enough, but throw a hot young babe onto his lap, and the whole pile would come tumbling down. He needed to leverage the properties—Christine gave me the names of the numerous entities through which she held them—and I could tell from the records at the registry of deeds that there was plenty of value to be tapped. He just couldn’t get at it without her signature, which she wasn’t about to provide.

The two of them were ushered into my office by Lenore, who asked them if they wanted anything to drink—she declined; , in an ingratiating tone, he said he’d take a bottle of water if that was all right. I nodded to Lenore, a signal that she could take the one I’d brought to work.

“Must be nice having a little practice like this,” Dalton said, looking around my humble rented quarters. “My lawyers—sheesh, you oughta see their digs!” I took this as male threat-posturing beneath a genial coat; he had expensive lawyers who would crush me if I tried to defend his wife’s interest with the zeal that the lawyer’s code of honor required.

“I can imagine,” I said, feeding him a little aw-shucks bait. It was fine with me if he thought I was just a good ol’ country lawyer. “I wouldn’t survive a minute in one of those big starchy firms,” I said, and I made it sound like an excuse. He looked me over, and from his goofy grin, I deduced that he thought I’d ended up where I was because I drank my way through law school, which was nowhere near the truth. I only drank on weekends back then. “Well, we might as well get started,” I said. “It looks like you two are going to go your separate ways, which is too bad, but it happens.”

“It’s not something I’m doing lightly,” he said.

“I’m sure that’s the case,” I said. I detected a roll of the eyes on the part of the distaff half of the marriage, but I plowed on through his manure. “We’ve got quite a tangled web to unweave here, don’t we?”

“Yeah, I guess you could say so. Of course, I built that up, so I know how to take it apart.”

“I’m sure you—and your lawyers—hold the magic keys to unlock all the doors.”

“I guess you could say that,” he said, again with a smile. I gathered I was dealing with a fellow who was used to getting his way.

“Is there some broad principle we could agree on to start the discussion?” I asked. I wanted him to lay his cards out on the table first.

“I think I’ve been perfectly clear on where I stand,” he said and turned to look at his wife, who took in his demeanor in less time than it takes a hummingbird to flap its wings. “We can part friends, or we can do this the hard way,” he said. You would expect those words to be spoken with bitterness but not in his case. He had no doubt stared down bankers and partners and mayors and others who stood in his path when he wanted to get something done, and this opening was probably as commonplace to him as a standard gambit is to a chess master.

I gave Christine a look—an upraised eyebrow, a nod of the head–one that we’d agreed on beforehand. I knew it would help things from a theatrical standpoint if she got up and left for a while as if overcome by the vapors or the fantods or whatever it was that ladies used to succumb to when the world started to get the better of them.

“Excuse me,” she said as she stood up. “If you two need to go over the list of properties, you can do that without me. I’m going to go pluck my eyebrows.” I took that to be the feminine equivalent of a guy saying he had to go see a man about a horse.

Once I was alone with Dalton, we tried out our best stares on each other like a couple of bull moose in rutting season. Neither of us gave any quarter, so it was time—as the kindergarten teachers say—to use our words.

“Your wife tells me you come from a very distinguished family,” I began.

“One of Virginia’s oldest and finest,” he said with undisguised pride. “Their only fault was they didn’t leave enough money for the current generation to lead a life of quiet contemplation.”

“You’ve really got to choose your ancestors carefully,” I said with a smile. “Of course, having that family name behind you must be like having the wind at your back as you sail through life.”

“Everybody around here knows who the Lunts were if that’s what you mean.”

“I figured as much. I imagine it helps open doors for you.”

“Sure, but once you get in, you’re on your own.” I must have overdone that naïve appearance strategy.

“Well, sure, but it’s getting in the door that means you always start in the red-zone of life while your competitors get the ball back on their own twenty—am I right?”

He smiled a sheepish little grin; I could imagine him wooing and winning Christine with the little boy look he was trying to sway me with now. “Yeah, sure.”

“It’d be awfully tough to lose that advantage—wouldn’t it?” I said a bit more sharply than before.

“Don’t think that’s gonna happen.”

“You never know. I hear that in polite society, cannibalism is still frowned upon.”

He swallowed visibly—and said nothing.

“It’s kinda funny,” I said. “Nose rings, tattoos—things you only expected to see on carneys and freaks back in the day are now socially acceptable while folks still get squeamish when they find out your ancestors ate their wives.”

“What the hell are you talking about?”

“You know what I’m talking about.” I made a show of picking up a file that didn’t contain all that much; George Percy’s account, a paper by the Jamestown archaeologist, microfilmed pages from newspaper archives. “The men in your family line seem to have an odd way of expressing their affection.”

“You son of a bitch.”

“I can imagine the membership committees of the Charlotte Hounds and the James River Hunt Club might take a dim view of a man whose family is only a few generations removed from—eating human flesh.”

“Nobody cares what happened hundreds of years ago.”

“They don’t? Are you kidding? That’s what clubs like that are for. To honor the dear old days of yore where losers like you acquire your tenuous claims to superiority in the here and now.”

“No need to get nasty.”

“Sorry, but it’s all a matter of public record or readily available secondary sources. I think it would be a wonderful thing if there were a website where schoolchildren could learn more about this fascinating aspect of the Old Dominion’s history.”

He sank into his chair softly but retained his pointed edge; I thought of him as a human meringue for a moment and decided to let him cool.

“You wouldn’t,” he said after a moment.

“I would.”

“That’s unethical.”

“You’re telling me what’s ethical? Why did you put the properties in Christine’s name in the first place?”

“That’s just good strategy.”

“I’m sure a family court judge would love to hear you explain that.”

He was silent again. I’d told Lenore not to let Christine back in until she heard the floor buzzer that ran from my desk to hers.

“What do you want?”

“I want you out of the family home as soon as possible. You both know what the properties are. You were too scared by your near-death experience in the last real estate crash, and your cash flow’s too tight for you to play cute, so you’ll play fair now that you know you have to.”

He nodded. “I really don’t like you.”

“That’s okay with me. To make it easy on us both, I’m going to refer Christine to somebody else for the divorce.”

“Why would you do that? Aren’t you lawyers all in it for the money?”

“I don’t need this kind of aggravation. I’ll just be hanging there like a brooding omnipresence . . .”

“What the hell’s that mean?”

“It’s an old Oliver Wendell Holmes gag—part of his stand-up routine. Anyway, I’ll be watching from the sidelines. I won’t get into the game unless Christine tells me she needs me. I won’t tell a soul about your, shall we say, peculiar family history—not even her new lawyer—unless you try to hurt her.”

I could tell he was defeated, so I shut up to let him vent if he needed to. Once you deliver the coup de grace, you can expect some groaning from the bull, but he just said, “What the hell’s taking her so long?”

“Don’t know; I’ll check.”

I stuck my head out the door, and Christine rose from the chair next to Lenore’s desk. I nodded my head back towards her husband, and she entered.

“Did you get lost or something?” Dalton asked her.

“I was having a nice conversation with Lenore out there. She has a rather uncanny system for playing the lottery.”

“Yes,” I said. “What she loses on each ticket she makes up in volume.”

“I’ve got to run, sweetie,” Dalton said. “I understand from your lawyer here that he can’t take your case.”

“What?”

“Looks like I have a conflict,” I said. “But I know someone whom you’ll like and who specializes in divorce. You don’t want to go to a heart surgeon who only performs one operation a year, and that’s sort of what I am when it comes to getting up on my hind legs in court.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” Christine said.

“Well, it was nice to meet you,” Dalton said as he extended his hand for me to shake.

“Same here,” I said. “Let me know if I can help you out with either of those clubs I mentioned.”

“Right,” he said and our eyes met and melded for more than a moment before he left.

“So what’s this about a conflict?” Christine asked when we were alone.

“That’s a little story we’re going to pretend is true. I told him what I knew about his family and how I’d use it if he tried to jerk you around.”

“Oh.”

“You really don’t want me to be your divorce lawyer, but I told him I’d remain an interested observer until the matter was resolved to your satisfaction.”

“Which means?”

“That he won’t try to claim the properties are his. I’ll talk to your new lawyer—she’s really sharp—and make sure she understands that everything is to be treated as marital property, right down the middle. Unless you want more.”

“No, I’m not vindictive. As long as the kids are taken care of.”

“That’s a different issue but he’s not going to put up a fight. If he does, I’ll get back involved.”

“Well, this has certainly been an adventure,” she said as she turned to go.

“I hope everything turns out all right—and I have a feeling it will.”

That was the last I saw of Christine, although I didn’t know it at the time. I got a Christmas card from her—nothing fancy, just a picture of her and her two daughters—and a bottle of wine, and that was that.

After she left, Lenore came back into my office to say she was going to the deli next door to get lunch— did I want her to get anything for me.

“The usual, I guess. Roast beef and coleslaw in a pita pocket.”

“You like it rare, right?”

“Actually,” I said as I thought back on the unique regional cuisine of Virginia, whose history I’d become so immersed in, “I’ll have it well done today.”

About the Author:

Con Chapman is a Boston-area writer whose work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Boston Globe, The Boston Herald, The Christian Science Monitor, and various literary magazines. He is the author of two novels, CannaCorn and Making Partner. His biography of Johnny Hodges, Duke Ellington’s long-time alto saxophone player, is forthcoming from Oxford University Press in 2019.