The roundabout road that led me to start digging deep at the Woody Guthrie Archives began well over forty years before the site opened. Yet it wasn’t the iconic folk singer’s legacy (nor that of his well-known son Arlo) that I focused on. Instead, I sought insight into Marjorie–Woody’s second wife–the lesser-known yet arguably most influential Guthrie of them all.

Through my early teaching years in the mid-’70s, I had read about Marjorie’s grassroots effort to educate and support families affected by Huntington’s disease, which debilitated Woody for well over ten years before his death in 1967. Her call to action inspired the students in my high school folk club to arrange a bake sale to raise money for the cause.

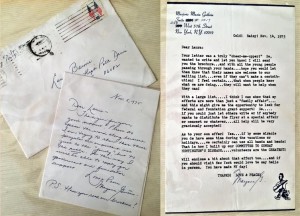

After we made the contribution, the students and I were thrilled to receive her personal reply, in which she reminded us that her project was “important not just to the ‘family’ [sic] but to the public.”

Lo and behold, about a week after receiving Marjorie’s thank you note, another letter arrived. She wrote, “with all the young people passing through your hands . . . hope you would let them know that their names are welcome to our mailing list. . . even if they can’t make a contribution! I feel certain . . . that when people know what we are doing . . . . they will want to help when they can!”

She explained, “a larger list might give me the opportunity to look for federal and foundation grant support!” (eventually, the organization became the pioneering Huntington Disease Society of America). She closed, saying “ . . . and if you should visit New York would love to say hello in person. You have made MY day!”

Intrigued by the woman and the cause, I vowed to keep up with her projects. Maybe take her up on her offer to visit the CCHD office in New York . . . sometime . . . after I married, I thought, busy in the midst of wedding plans and teaching. In 1983, I read about Marjorie’s death from cancer at age sixty-five. I had missed my chance to meet her, but her sense of service stuck with me; I was a thirty-something “flower-child” still grounded in the idealism of the sixties that had motivated me to canvas the streets of Hartford in support of peace candidate Eugene McCarthy in 1968, strike in protest after Kent State in 1970, and organize Hartford’s first twenty-five-mile March Against Hunger in 1971.

Shortly after Marjorie’s death, I read Joe Klein’s biography Woody Guthrie: A Life. With a mention of Marjorie here and there, it reacquainted me with her as Woody’s second wife and mother to four of his children (their first died in a tragic accident at age four). I learned that she had danced with the renowned Martha Graham in the forties and fifties. I was struck by how, even after their divorce, she managed his health care from hospital to hospital, for over fifteen years. Marjorie accomplished all this while raising their three children and working full time as a dance teacher at her own studio in Brooklyn, New York.

I spent the next dozen or so years raising my children, teaching part-time, and then I returned to full-time teaching in 1996. This left little time for reflection on myself, much less Marjorie. Until in 1998, the clock seemed to stop; my husband died suddenly. Overnight, I had become a single mom, and in the inexplicable way a mind works, thoughts about Marjorie raising her three children during Woody’s long convalescence and after his death regularly surfaced in my stream of consciousness.

Working full-time while raising two grieving children through adolescence consumed my every minute and, in a convoluted way, prevented grief from consuming me. I finally got to read Ramblin’ Man, Ed Cray’s 2004 biography of Woody. A single chapter focused on Marjorie. It was not enough to fully flesh out Klein’s sketch of her but enough to reignite my curiosity to find out more–if I only had the time.

While getting my MFA at Western Connecticut State University, I began working on an enrichment project on American folk music. More information about Marjorie’s dance career came to light. However, the work on my final thesis–a memoir of loss and recovery about my family’s tragic loss–took precedence. A year after my memoir was published, I longed for another serious writing project. In a typical one-click-leads-to-another Internet search, I discovered that an official Woody Guthrie Archive was opening in the spring of 2013 in Tulsa, Oklahoma. This piqued my interest, since I had already exhausted every secondary source about the Guthries I could get my hands on, in print and online.

Around this time, a close friend asked, “What do you want to write?”

I blurted, “I really want to write a biography about Marjorie Guthrie,” realizing it to be true.

With an official archive now accessible, was this now possible? Yes and no.

Although a full listing of the archive’s collections is available online, the actual sources are not. This meant I would have to travel to Tulsa, 1,500 miles away–an expensive proposition.

The Woody Guthrie Center website also offered information about an annual fellowship to support research at the Tulsa site. I applied, and eight weeks later, received notice I had not been awarded the fellowship. Once I put aside my initial disappointment, the sentence that welcomed me to continue my research at the archives resonated. Why not? I thought and started a “Tulsa or Bust” fund. A year later, I spent a week in Tulsa sorting through correspondences, news articles, and tapes of interviews.

To say I was overwhelmed by this 2015 trip would be understatement. Even with the guidance of Kate Blalack, the helpful archivist at the center, I had no idea how time-consuming it would be to read deteriorating papers or how exacting this work would be.

Kate greeted me warmly as we sat down for my preliminary interview. As we talked, Kate agreed that Marjorie had been overlooked in the Guthrie legacy, especially since it was Marjorie who first began collecting what fills the archives today and it was Marjorie who did groundbreaking work for the Huntington’s Disease Foundation.

The next day, I began digging. Kate supplied me with automatic pencils (no ink was allowed near the documents), a yellow legal pad, a flat tool to turn pages (to keep the oils from my washed hands from compromising the papers), and a magnifying glass. I started with the first box of the Woody Guthrie Correspondence Collection, some of which contained letters Woody sent to Marjorie during his Merchant Marines days and Marjorie’s first pregnancy. He wrote to her daily, sometimes hourly, professing his love and discussing his politics. Although Woody’s letters alluded to her replies, Marjorie’s letters did not appear in this collection (or any other onsite). I wondered why as I tried to figure out as much as I could about their two-way interactions, using only his letters.

I expected to get through boxes and boxes of artifacts during my week at the Woody Guthrie Center. Instead, I tackled only one box. During the week, my pencil-written notes were secured in my locker overnight until my last visit, at which time my week’s worth of notes was photo-copied for the archive records. And even with my bounty of information, I would still have to apply for permission to use the material in published writing. Severe standards, one might say, until realizing archives offer full disclosures of families’ lives, lives whose histories are a privilege to share.

I left Tulsa physically and mentally exhausted yet oddly committed to do that again sometime. I can only liken it to the rigors runners put themselves through–voluntarily–when they take on a marathon and–a day or two later–start to plan their next twenty-six-mile run. My archival research was a mental marathon, and I was already looking toward repeating the long-distance event.

I applied once again for the grant money in the spring of 2016, with a much more focused letter of application and a complete book proposal. This time, I was named a 2016 recipient of the eleventh Annual Broadcast Music Incorporated Woody Guthrie Fellowship. My second week in Tulsa this past summer proved much more productive. I found myself more focused, taking time to be moved by correspondences and even documents: the marriage certificate, the divorce certificate, the hospital admissions and doctors’ reports, Woody’s death certificate–a whole quarter of a century of a married couple’s life together assembled in a single box of brittle papers.

I had read about Woody’s physical deterioration from Huntington’s Disease in the Klein and Cray biographies. Even during their subsequent marriages, Marjorie would bring Woody home from a distant hospital for weekend visits. When he could no longer make the trip, she traveled with the children to his bedside. She drew cards for him stating “YES,” “NO,” and “?” to help him communicate when he could no longer speak. The official hospital reports I found revealed, in clinical detail, the steady progression of his disease with which Marjorie had to cope. She documented everything, from his “random uncontrollable jerks” in April of 1961 to his “severely deteriorated state,” which rendered him bedbound at the New York State Hospital, unable to a communicate with anything other than “high-pitched groans” in June of 1966. In addition, an official doctor’s report documented the heartbreaking perception that “He seems to perceive and suffer from his own helplessness.” Information like this caused me to leave my second trip to Tulsa not only physically and mentally exhausted but also emotionally exhausted.

Through both visits to the archives, I became a connection-maker as well as a note-taker; I became more and more conversant about all things Marjorie. Kate and I would find and discuss photographs of what appeared to be Marjorie’s fragile beauty onstage, though she bore her rigorous dance regimens with remarkable strength. I passed on information to Kate and introduced her to sources the archives did not contain, such as Aaron Lansky’s Outwitting History, in which he chronicles his seventies’ mission to rescue over one million Yiddish books from extinction with Marjorie’s help. Kate and I shared frustration over the absence of letters penned by Marjorie. However, I located her letters to folklorist Richard Reuss in a collection at the Indiana University. We are in the process of trying to attain copies. And a new conversation started when Kate arranged for me to interview folklorist Guy Logsdon and his wife Phyllis, friends of Marjorie, who assisted her when she traveled to Oklahoma to connect with families of Huntington’s victims. This interview is now available at the archives.

I can’t help thinking back to Marjorie’s 1975 letter reminding me that her activism was “important not just to the ‘family’ but to the public.” Forty years later I would begin to discover, through my research at the archive, the full purport of these words on other aspects of Marjorie’s life as well: her dance career, her political and creative influence on Woody, and her efforts to secure his legacy. There are more researching and conversing ahead: another trip to Tulsa with the remaining grant money, more digging at the New York Public Library of Performing Arts, and visits with students and colleagues who were fortunate enough to have Marjorie involved in their lives and their projects. As with the marathon runner, the road goes on and on and on. There is no turning back now, just a bit more sure-footedness on the journey ahead.

**

Special thanks to the BMI Woody Guthrie Fellowship Program, Woody Guthrie Publications, and the Woody Guthrie Center for supporting the research and development of this article.